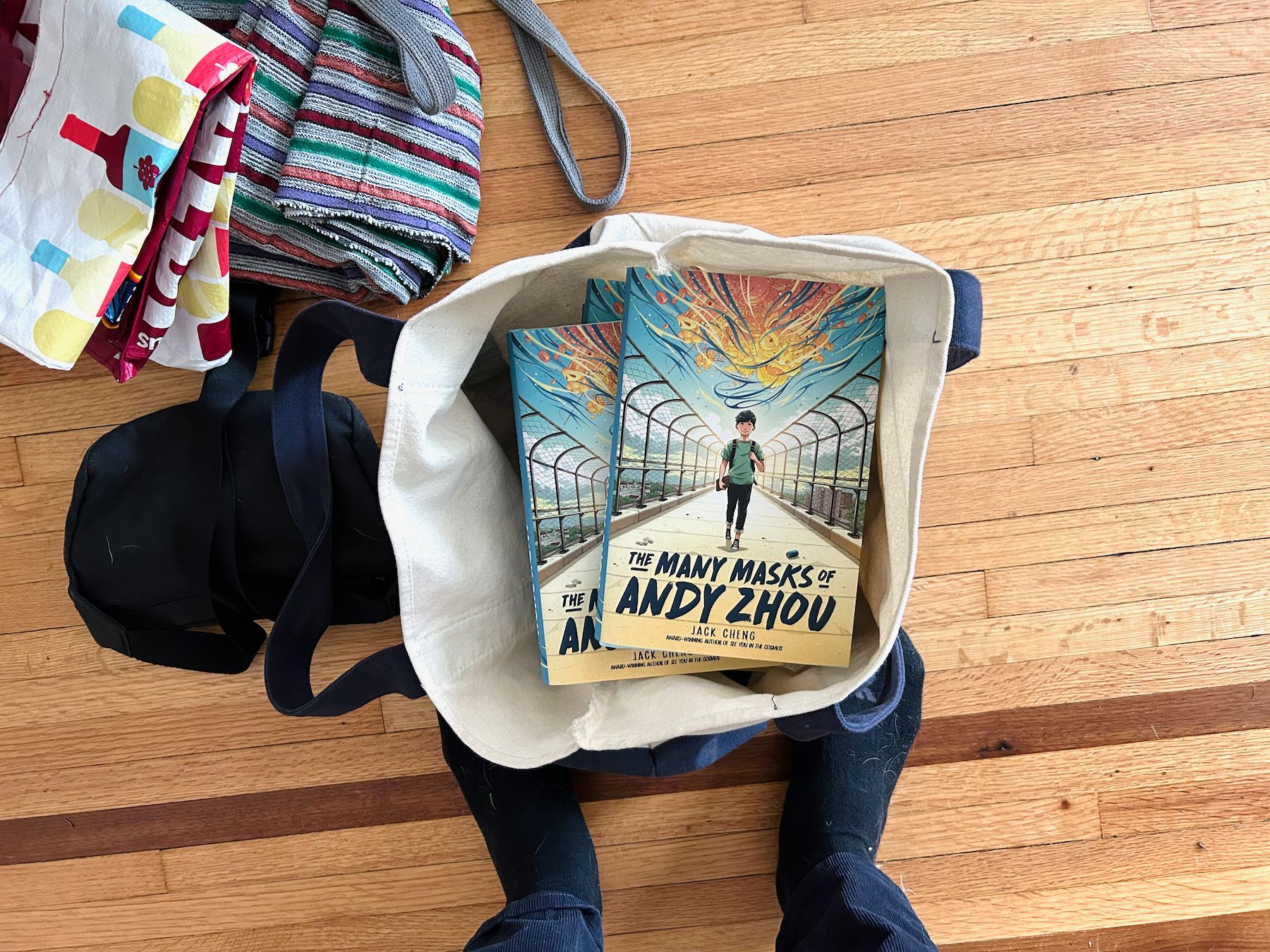

My author copies of the new book arrived in the mail last week. The batch pictured above was gifted to a group of students from Ferndale Middle School who gave feedback on a draft last summer. There are some subtle differences between that draft and the printed hardcover, and one not-so-subtle one: The finished book contains 42 of my own illustrations, appearing at the start of each chapter, like so:

Did I mention you can pre-order the book before its June 6 release?

I spoke (or typed, as it was a written interview) to Publisher’s Weekly recently about the book as part of a piece for AAPI month. One question drew out some simmering thoughts I’ve had about regionality:

How did you approach including the specificity of Chinese American culture in Andy’s experience?

Specificity, to me, is what makes fiction come alive. I’m always looking for little details and idiosyncrasies that help make characters or places feel more real or vivid. Many scenes in this book are based on personal experiences, and with those, the challenge was often in what to leave out.

As far as the particularities of Andy’s Chinese American experience, I can’t fathom not getting regional, as both China and the U.S. are so geographically diverse. Andy’s family, like mine, emigrated from Shanghai, and that comes out in their dialogue and the food that his Hao Bu (paternal grandmother) makes. The story is also set in present-day suburban Detroit, which has a distinctly different vibe than coastal cities with larger Chinese populations or rural areas with very few Asian people. So it’s a Chinese American experience, but it’s also a Shanghainese American one, and a Shanghainese Midwestern one.

That’s the first time I’ve uttered/written the phrase Shanghainese Midwestern, and it feels right on.

I was also a part Detroit Public Television’s AAPI Stories series, which aims to showcase some of the Midwestern Asian American experience through StoryCorps-like interviews between friends or family members. I sat down with my friend Paul, who I only met couple of years ago, but who I’ve gotten to know on a deep level through conversations just like the one we had on camera.

The interview was filmed in my living room this past winter, and in the background and some of the B-roll footage you can see shots of my neighborhood and the architectural models for my home design project. In the segment below, I connected the dots for the first time between placemaking (in an urban planning sense) and my feelings of in-betweenness as a Chinese American.

You can watch the full thing here.

Last week also saw the Disney+ premiere of American Born Chinese, adapted from Gene Luen Yang’s Printz Award winning graphic novel. I didn’t read the book until long after it came out in 2006, and the first time I read it I found it almost triggering. I saw so much of my younger self in the main character, Jin; I cringed at his painfully familiar actions and attitudes, I rooted for his growth. The feelings it dredged up are some of the same feelings I’m exploring in my own book.

I think this New York Times piece gets something right about the timing of the series adaptation. This show in its current version couldn’t have happened without Everything Everywhere All At Once and all that led up to it. When Julia and I sat down to watch the first episode, I caught myself mimicking Jin(acted brilliantly by Ben Wang)’s facial expressions. I can’t recall the last time I did that for a show or film. Talk about a powerful mirror.

When authors and filmmakers tell stories like these, we’re hoping they’ll become such mirrors, yes. But we’re also hoping that, as the saying goes, they’ll be windows or sliding glass doors for audiences who don’t look like us, and who have different experiences. Gene was the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature a few years back, and his inaugural speech in that role is all about this power inherent in great stories. I encourage you to read it.