For those just coming across these letters, I’m currently writing about my experience as a student in Building Beauty, a two-semester architecture program based on Christopher Alexander’s The Nature of Order.

Weeks 3 & 4. What is the world made of? That was the question posed at the beginning of one of recent discussions. The mechanistic, Cartesian answer might be something along the lines of “ever-smaller components” – parts, cells, molecules, atoms, quarks … and so forth.

One of my classmates said “energy.“ A different classmate and I said relationships, interactions. To Alexander, a first answer might be wholeness (or wholes).

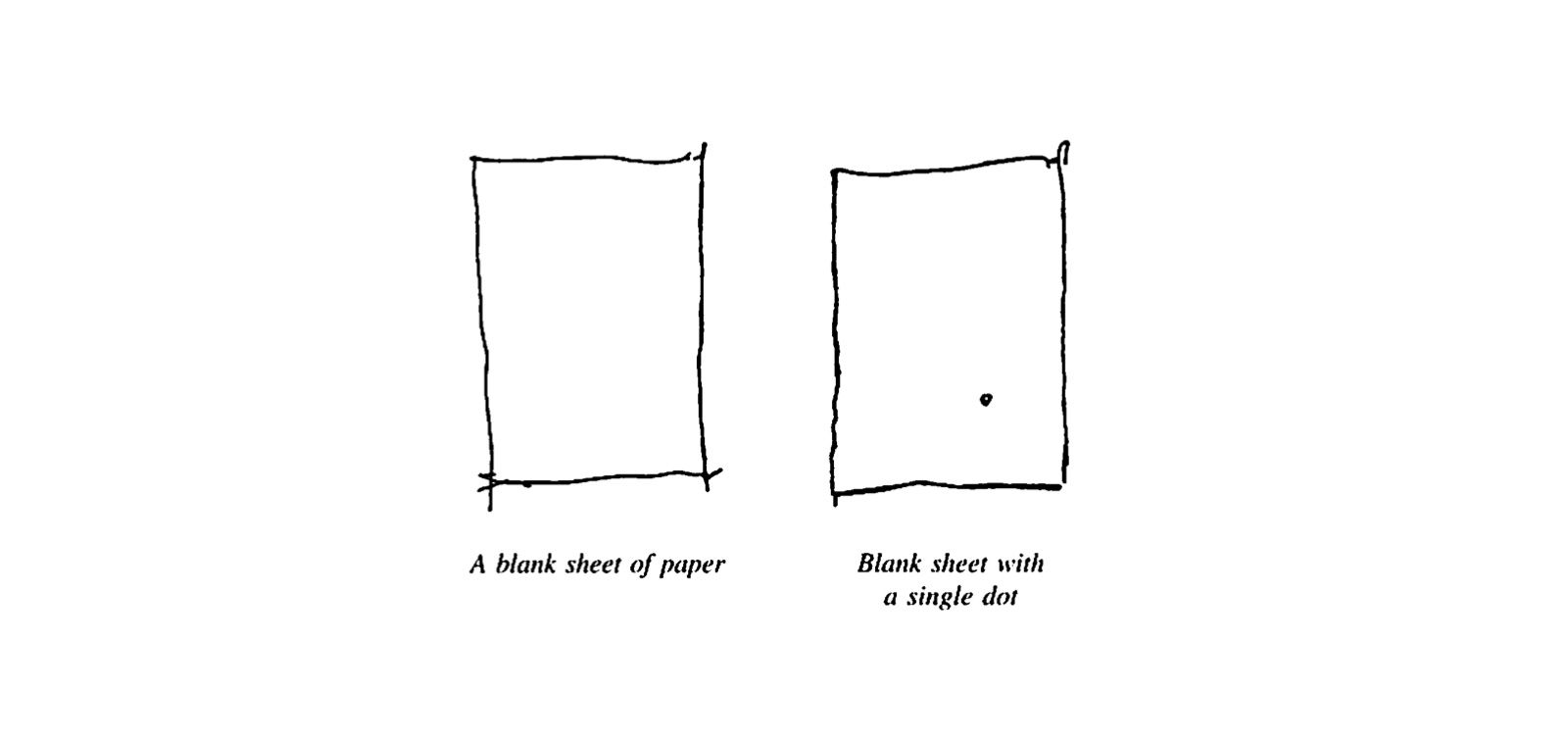

I poked at a definition of wholeness last time – aliveness, freedom, comfort, that “quality without a name.” Alexander show the idea of wholeness most simply by drawing a blank sheet of paper and putting a dot on it:

The blank sheet on the left, he says, has a certain kind of wholeness. It has a certain character or feeling. Once the dot’s introduced, the wholeness changes. The gestalt of the page changes. And – here’s where it gets interesting – it’s this new wholeness that brings out previously hidden entities in the page.

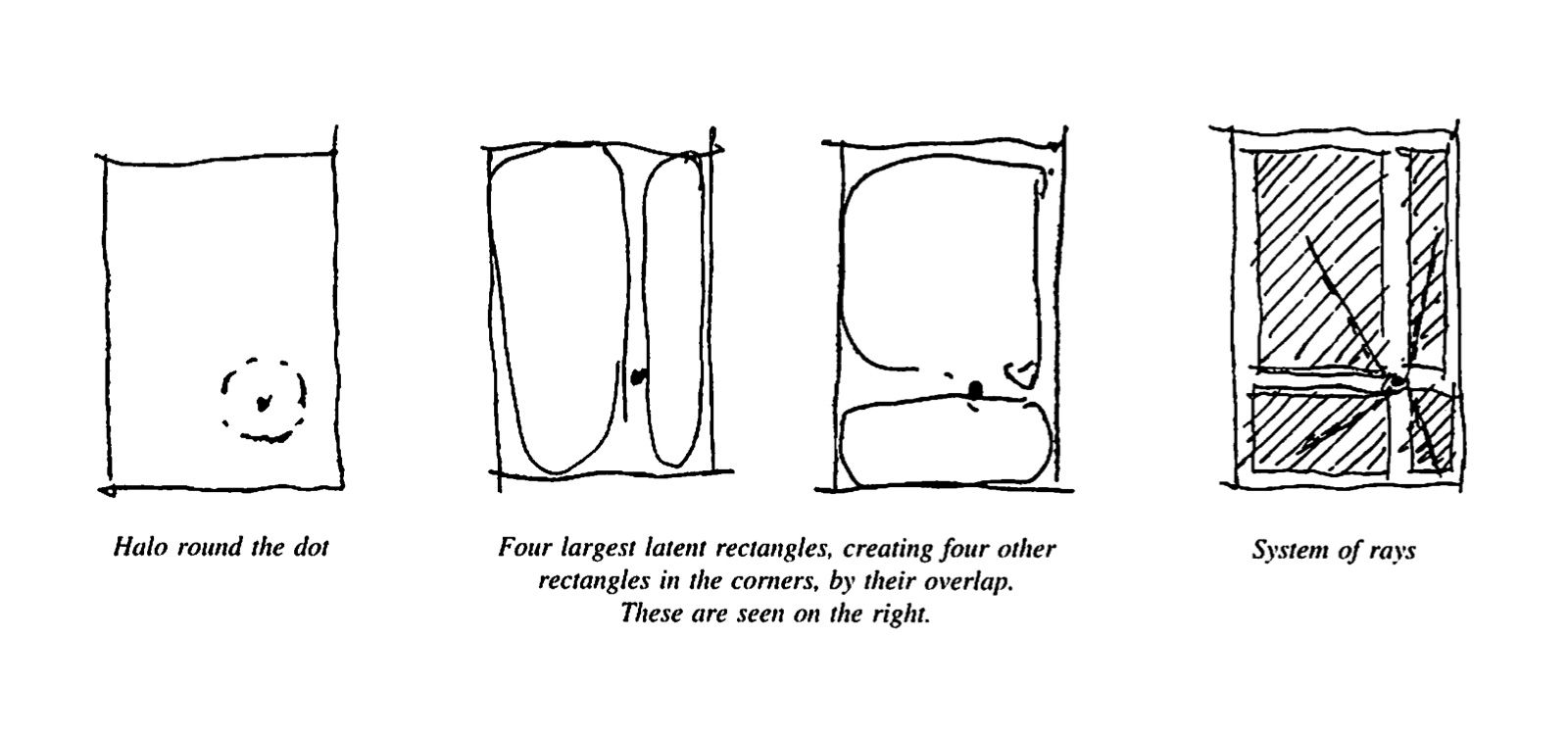

If you stare at the dot, it feels like there’s almost a halo in the negative space around it. You might then start seeing the page subdivided into quadrants, the way that putting a pillar in an empty room might suggest subsections of space. The dot also forms a relationship with the corners, subtle rays projecting outward toward them. Alexander diagrams these out:

These “parts” aren’t assembled in a mechanical sense. It goes the other way around – they emerge from the new wholeness that’s created with the addition of the dot. Alexander puts “parts” in quotes because they’re not parts in the mechanical sense – you don’t put them all together to create the new whole.

It helps, though, to be able to point them out and gauge how much they are contributing to the wholeness of whatever it is we’re looking at. In the example of the room and pillar, the main activity of the room happens in these very zones suggested by the introduction of the pillar. We need a better word than “part” or “zone” – a word that also can be used to describe the pillar itself, too. The word that Alexander picks is center.

It might seem like an odd choice at first: why, not say, element or entity? Or even the word whole, to connect with the quality of wholeness? Because those words are too bounded:

From the point of view of relationshps which appears in the design, it is more useful to call the kitchen sink a “center” than a whole. If I call it a whole, it then exists in my mind as an isolated object. But if I call it a center, it already tells me something extra; it creates a sense, in my mind, of the way the sink is going to work in the kitchen […] It makes the sink feel more like a thing which radiates out, extends beyon its own boundaries, and takes its part in the kitchen as a whole.

So not center-in-the-middle, but center-as-an-organized-zone-of-space. It’s also imprecise to think of, say, a pond as a discrete object when its boundaries are fuzzy. The water’s a part of a pond but what about the clay underneath or the leaves floating on top? Where do you draw the line of where the shore ends and land begins?

Calling a pond a center is appropriately fuzzy. Each center then, is made up of other centers, each fuzzy itself but also a concentrated patch of physical space. The word center is, to me, an elegant linguistic hack that Alexander uses to get us to see context, something that the mechanized worldview makes it hard for us to see.

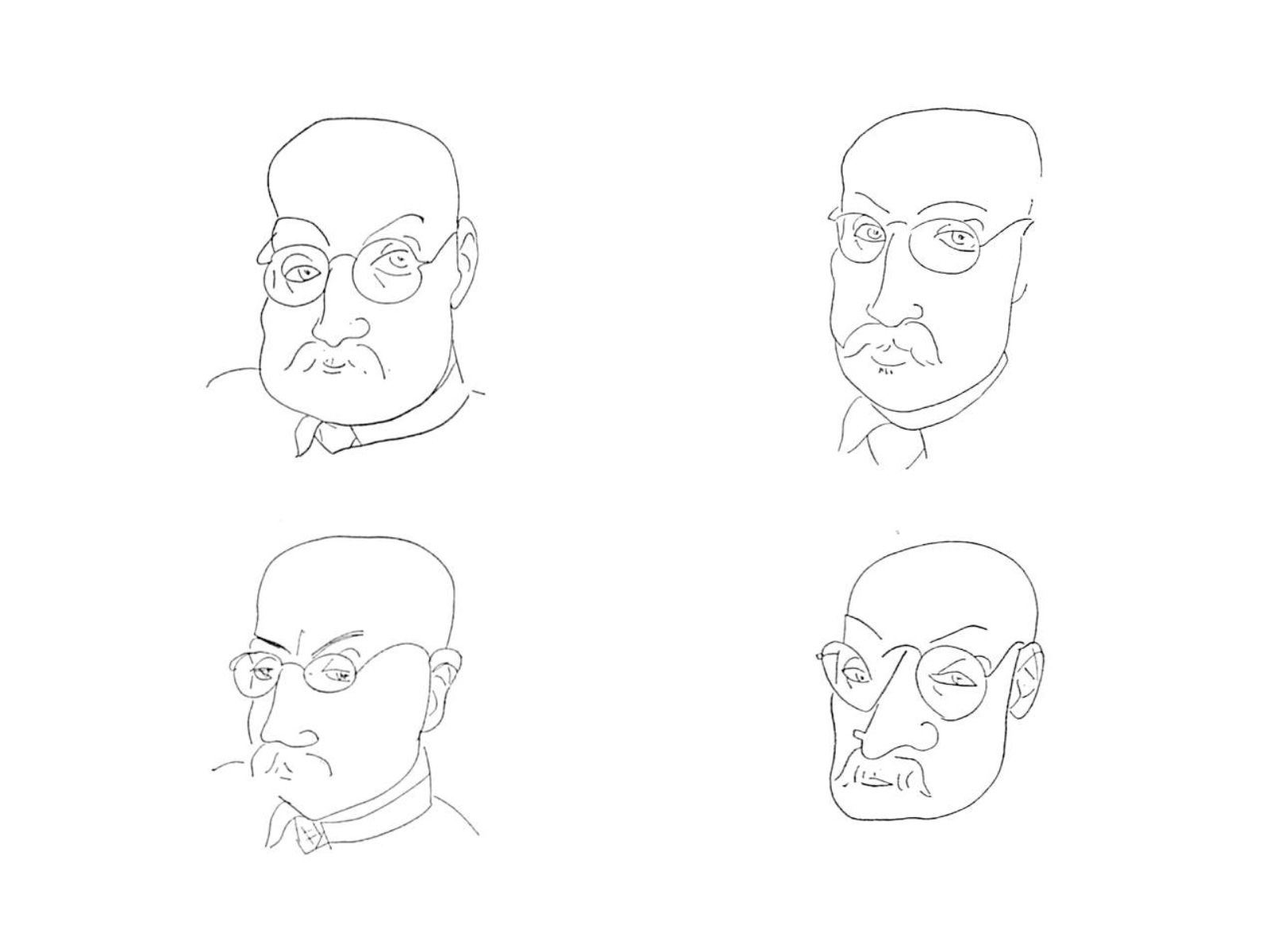

I’m realize I’m at risk of sounding jargony, so here’s the example he presents that best cleared it up for me, from Henri Matisse’s essay for a 1948 restrospective at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In it, Matisse talks about how the character of a face is deep within a person and can’t be captured by their particular features. He draws four different self portraits:

Here’s Alexander, summarizing:

The features, in a normal sense, are diferent in each drawing. In one he has a weak chin, in another a very strong chin. In one he has a huge roman nose, in another a small pudgy nose. In one the eyes are far apart, in another they are close together. And yet, in each of the four faces, we see the unmistakable face and character of Henri Matisse.

Character here is another word for wholeness. The wholeness of a space is its [good] character. And it comes not out of the individual features themselves but of their overall structure and spatial relationship—the field of centers. The world, Alexander might say, is made of centers, each with their own centers. It’s recursive, rather than atomic.

Okay, no more vocab for now. Next week I’ll show some fun stuff: the result of my first studio project.