It was while I was traveling this summer that I first started to appreciate the hangover. There would be nights in Japan when DB and I would go out and, as one does, end up drinking a little too much. But we’d still do things the next day – go see temples and castles and museums. We’d still do more or less what we had planned.

Those hangovers felt different than the usual ones. Not just from the activity but also, I think, from the openness lent by traveling. I was more amused at, and aware of, the shape of those hangovers; I discovered that in the midst of them I could do certain things – like people-watch or read a book – perfectly well, and others – like construct coherent sentences – not so well at all. There, on the road, the hangover wasn’t something to be gotten rid of; it was part of the whole experience.

It feels strange to type this: those hangovers are probably my biggest lesson from the two weeks in Japan. I’ve been using “appreciating the hangover” has a shorthand for acknowledging that the so-called “bad” parts are inseparable from the greater experience. They’re part of what I signed up for. When you drink, there are going to be times when you drink a little too much. When you decide to live by yourself, there are going to be nights when you feel a little lonely. When you write a weekly newsletter, there are going to be moments when you feel guilty for not sending it on time. Each decision carries with it its own set of unknowns and not-immediately-apparent downsides. If we see these more as a part of a choice that we made, we give ourselves more agency. We can become more curious about the hangover-energy, or the loneliness-energy, and work with it, transform it.

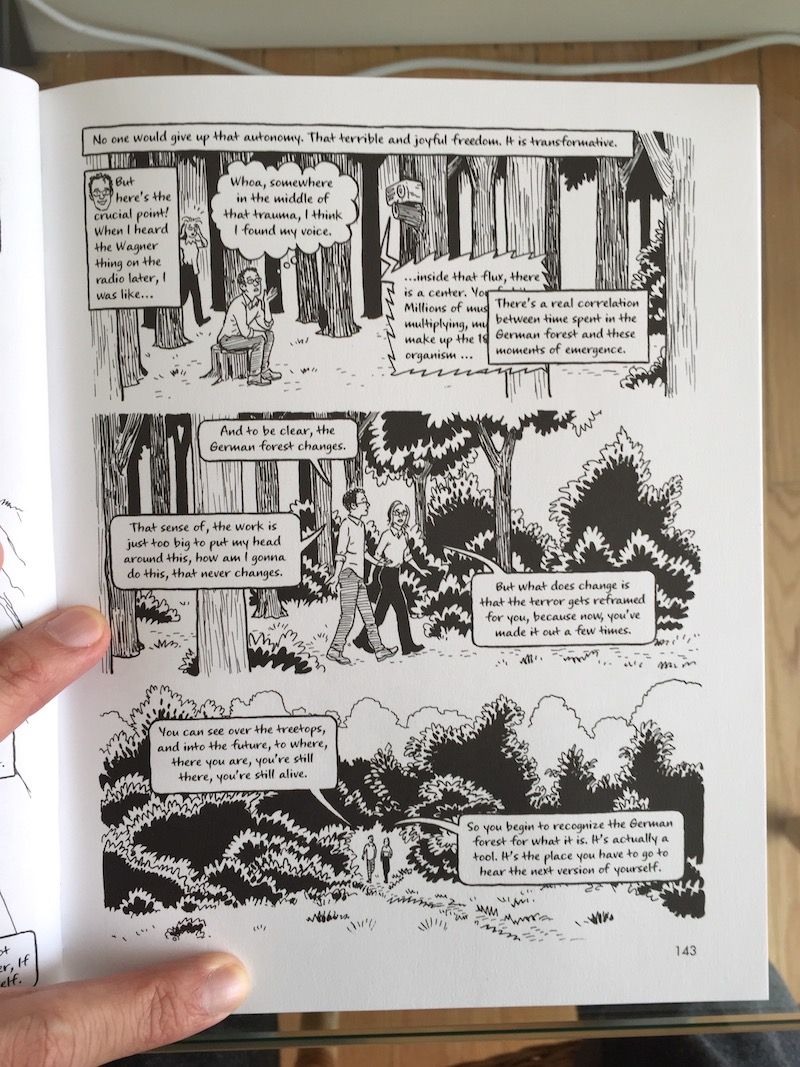

Yesterday I read Jessica Abel’s Out on the Wire, a graphic narrative (is there a better word for nonfictional book-length comics?) about how some of the top radio producers tell their stories. In one part, various producers are talking about the moment of creative overwhelm in a project – the pressure of deadlines and struggling to make something as good as you think it should be. It’s a feeling of not just being lost in the woods, but in a deep and endless wood; the Radiolab guys call it “the German forest”. The same freedom and autonomy, Jad Abumrad says, that makes these radio shows good, is also what puts you into the German forest: